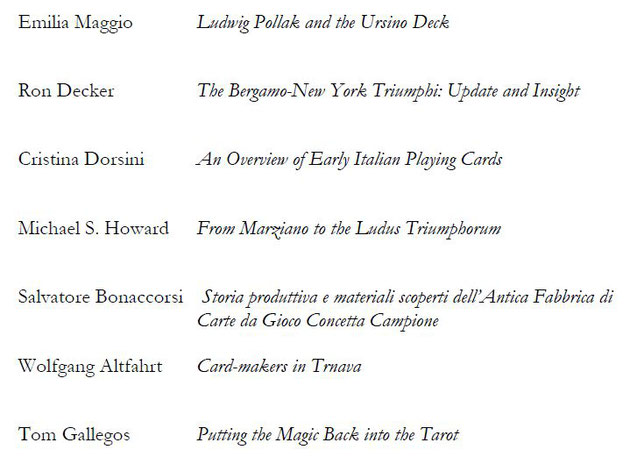

CONVENTION PAPERS

LUDWIG POLLAK AND THE URSINO DECK

di Emilia Maggio

Abstract italiano

Nell’autunno del 2014, un’impiegata del Museo Civico di Castello Ursino, scoprì una serie di fogli dattiloscritti contenenti la descrizione dettagliata delle 15 carte miniate della Collezione Biscari, note come i « Tarocchi di Alessandro Sforza ». L’autore del documento era Ludovico Pollak, archeologo ed esperto d’arte di origine ceca, consulente dei grandi collezionisti europei e americani del periodo tra il XIX e il XX secolo. Scritta nel 1925, pochi anni prima che la Collezione Biscari fosse trasferita all’attuale sede di Castello Ursino, la descrizione doveva essere inserita nel catalogo della Collezione, catalogo al quale Pollak lavorava insieme a Guido Libertini. Quest’ultimo si occupava della parte archeologica, che fu poi pubblicata; ma il lavoro di Pollak sui meno conosciuti oggetti di età post-antica (tra i quali figuravano, appunto, i « Tarocchi di Alessandro Sforza ») non fu mai dato alle stampe. La sua descrizione dei tarocchi, intitolata semplicemente « Appunti e studi di Ludovico Pollak sulle carte da giuoco quattrocentesche del Museo Biscari », costituisce l’analisi più completa di questo antico mazzo, osservato prima del restauro (1987), quando un passepartout indelebile fu applicato a ogni carta, nascondendo completamente il retro. In uno di questi retri, Pollak aveva notato un’abrasione, sotto la quale si scorgevano tracce di scrittura a inchiostro con la data 1428, indizio utile per assegnare l’esecuzione del mazzo intorno alla prima metà del XV secolo.

Visto che la stessa data compare su uno degli strati di carta riciclata che formano l’interno del quattrocentesco « Tarocco dell’Imperatrice » della Collezione Abatellis, simile per stile e dimensioni alle carte Ursino, è stato possibile confermare la sua appartenenza a quel mazzo, dal quale mancano, tra l’altro, oltre, appunto, all’Imperatrice, anche il Due di Bastoni, altra carta miniata proveniente della Collezione Abatellis. Oltre a un breve resoconto della vita e dell’opera di Ludovico Pollak e delle circostanze in cui furono scritte le schede del mazzo Ursino, il presente articolo comprende la traduzione (dall’originale italiano) di questo importante documento, a beneficio degli studiosi internazionali di antiche carte da gioco.

English abstract

In the Autumn of 2014, staff at the Castello Ursino museum discovered a typescript containing a detailed description of the fifteen illuminated playing cards making up the so-called Alessandro Sforza Tarot from the Biscari Collection. The author of this document is Ludwig Pollak, the Czech archaeologist and art connoisseur who advised the best-known European and American collectors between the 19th and the 20th century. Written in 1925, just a few years before the Biscari Collection was moved to its present location at Castello Ursino, the description was intended to form part of a catalogue which Pollak worked on together with Guido Libertini. Unlike Libertini's section on the archaeological pieces, Pollak's work on the lesser-known post-antique items (including the Alessandro Sforza Tarot) was never published. His description of the Ursino deck is entitled « Appunti e studi di Ludovico Pollak sulle carte da giuoco quattrocentesche del Museo Biscari » (Notes and studies by Ludwig Pollak on the 15th-century playing cards at Museo Biscari). So far the most thorough analysis of this early deck, the description is particularly interesting because the cards are observed prior to their restoration (1987), when an indelible paper mount was applied to each, obliterating the view of the backs. On one of these backs, in fact, Pollak had noticed an abrasion exposing traces of writing in ink that included the date 1428, an indication that the making of the set could be assigned to roughly the mid-15th century. As the same date appears on one of the inner paper layers of the Empress from the Abatellis collection, a card similar in style and size to those from the Ursino set, it has been possible to confirm its belonging to that deck, particularly as the Empress, as well as a companion card (the Two of Clubs), are among the missing ones from the Ursino series. Beside an account of Ludwig Pollak’s life and legacy, and the circumstances of the production of his entries for the Ursino set, this article includes an English translation (from the

original Italian) of this seminal document, for the benefit of early playing cards scholars worldwide.

Complete text in english

Nearly a century ago, in February 1925, Catania’s Museo Biscari was visited by Ludwig Pollak, the internationally renowned archaeologist and art connoisseur. This was just a few years before the Museum’s collection was moved to its present location in Castello Ursino.

The huge collection of sculptures, mosaics, paintings, applied arts and natural history had been put together by Ignazio Paternò Castello, 5th Prince of Biscari, who had mostly come into possession of the pieces from his archaeological excavations in and around Catania; other objects he had purchased on the antiquarian market, both in Sicily and during his travels throughout Italy. Prince Biscari had committed himself to publicly display all these pieces regardless of expense, so he had a purpose-built wing added to his palace, where the collection was exhibited from 1756 to 1925.

At the Museo Biscari, Ludwig Pollak collaborated with Guido Libertini to compile a comprehensive catalogue of the prince’s collection: while Libertini dealt with the archaeological pieces, Pollak dedicated himself to the later works, including the 15 playing cards currently known as the "Alessandro Sforza Tarot". Libertini’s catalogue was published in 1930 but Pollak’s volume remained unfinished. A number of his manuscripts are kept in Rome, at the Museo Barracco, but the one relating to the "Alessandro Sforza Tarot" was accidentally found in the archives of Castello Ursino in the Autumn of 2014. The text is typed but the title page is handwritten and reads: "Appunti e studi di Ludovico Pollak sulle carte da giuoco quattrocentesche del Museo Biscari" (Notes and studies by Ludwig Pollak on the 15th-century playing cards at Museo Biscari). The whole document is written in Italian, a language Ludwig Pollak was conversant with because of his studies and his many Italian friendships, which were connected with his work as a classical archaeologist and art dealer.

Each of the 15 cards making up the incomplete "Alessandro Sforza Tarot" is described in detail. The main interest of this text lies in that the observation of the cards pre-dates their restoration by ICPAL (Istituto Centrale per la Patologia del Libro, Rome) in 1987, when an indelible paper mount was applied to each, thus obliterating the view of the backs. In fact, on the back of the Stag Rider (here called "Allegoria della Temperanza", though Pollak also expresses some doubts about this interpretation) there is an abrasion showing some of the recycled paper that forms the inner layering of the card. On it, the date 1428 is visible, providing a terminus post quem, which suggests that the making of the set can be assigned to the first half of the 15th century. More interesting still, the same date appears on one of the inner layers of another card, the Empress from the Abatellis collection, Palermo. Given the similarity in style and dimensions between this and the Ursino cards, it has thus been possible to confirm their belonging to the same set, particularly as the Empress and a similarly-formatted Two of Clubs also found in the Abatellis hoard, are among the missing ones from the Ursino series.

No doubt Ludwig Pollak would be very pleased about this discovery, particularly as this provides a further opportunity to remember him and his legacy after the exhibition held in Rome earlier this year. On display at the Museo di Scultura Antica Giovanni Barracco and the Museo Ebraico were items from his personal collection, including paintings, antique sculptures and pottery, watercolours, rare books and travel photographs. These objects documented the life of an internationally renowned art dealer who advised the greatest collectors of his time: the entrepreneur and philanthropist Edmond James de Rothschild; Carl Jacobsen, owner of the Carlsberg Breweries and founder of Copenhagen’s Glyptotek; John Pierpont Morgan, the American banker, whose eclectic collection is now open to the public as the Morgan Library and Museum (it includes, incidentally, a set of Visconti-Sforza Tarot cards, one of the most complete 15th-century decks). Pollak was also a friend of Emanuel Löwy, the classical archaeologist, who introduced him to Sigmund Freud, who also had a collection of antiques that Pollak then helped classify.

Ludwig Pollak had been born near Prague’s old ghetto in 1868, of a modest family of Jewish cloth merchants. He studied classics at the Gymnasium and read archaeology and art history at Prague’s prestigious University. From there he moved to Vienna, to perfect his skills as an archaeologist. He then furthered his education in Rome and Athens, eventually choosing Rome as his residence (from 1893).

As an archaeologist, Pollak’s main claim to fame rests upon his discoveries in the field of ancient sculpture, particularly that of the lost arm of the statue of Laocoon, which he presented to the Vatican in 1903, and for which he was awarded the Order of Merit by Pope Pius X: it was the first time a non-converted Jew was given an award by a pope. Given his achievements, as well as his prominent position in the international cultural milieu, it seems extraordinary that today his name should be so little known.

One reason for this was the consequence of a law passed in 1909 granting the Italian State first option to buy any goods of archaeological, historical or artistic interest to be found in the national territory. Pollak was involved in a couple of scandals linked to his presumably illegal export of antiques. The allegations proved groundless but these incidents demonstrated the difficulty for him to continue to operate as both an archaeologist and an art dealer in Italy, particularly as some of his long-established clients and friends happened to pass away during those years.

Another reason that eventually led to the oblivion suffered by Pollak was the progressive marginalisation of Jews from public life which affected the European cultural climate between the two Wars. During WWI Pollak and his family had moved from Rome to Switzerland, then Prague and Vienna, where Pollak met Sigmund Freud (with whom he would establish a lasting friendship based on a shared interest in both archaeology and Goethe). As he had served in the Austro-Hungarian army during the war, Pollak’s house in Rome was confiscated by the Italian government, together with the rest of his property. Nevertheless, Pollak was able to return to Rome, where he formed strong bonds with the Jewish community, both Roman and international. As a consequence of Hitler coming to power, Pollak was then expelled from Rome’s Biblioteca Hertziana: this important research institute, founded by Jews, was now being run by the Nazi. When Mussolini too introduced racial policies, Pollak began to dispose of his collections through auction sales, as well as donations to Geneva’s Art and History Museum. Despite being offered shelter within the Vatican, Pollak decided to embrace the fate of his people. However, he also seems to have doubted the Nazi would be interested in deporting such an old man, but his assumption proved wrong. Most of the prisoners taken from Rome to Auschwitz-Birkenau in the October of 1943 were gassed immediately. Nothing more precise has been found about the end of Ludwig Pollak, his wife and their two children. The Jewish community in Rome had lost track of them because there were no family members left. In fact, the only survivor was Pollak’s sister-in-law, who later donated his personal collection to the City of Rome.

The typescript with the "Notes on the 15th-century playing cards at the Museo Biscari" is the basis for one of the entries in the museum’s catalogue, which was going to be the result of the joint effort of Guido Libertini (who would later move the Biscari collection to its present location at Castello Ursino) and Ludwig Pollak. The latter’s contribution to the catalogue, which would contain the cards’ description, was never published. As in 1925, the year of his visit to Catania, Pollak’s career was already on the decline, the Sicilian project had to be put aside, awaiting better times; and it can only be imagined how regretfully. Now the "Appunti", which also include a rich bibliography, are finally seeing the light, both in their original Italian version and in English, for the benefit of early playing cards scholars worldwide.

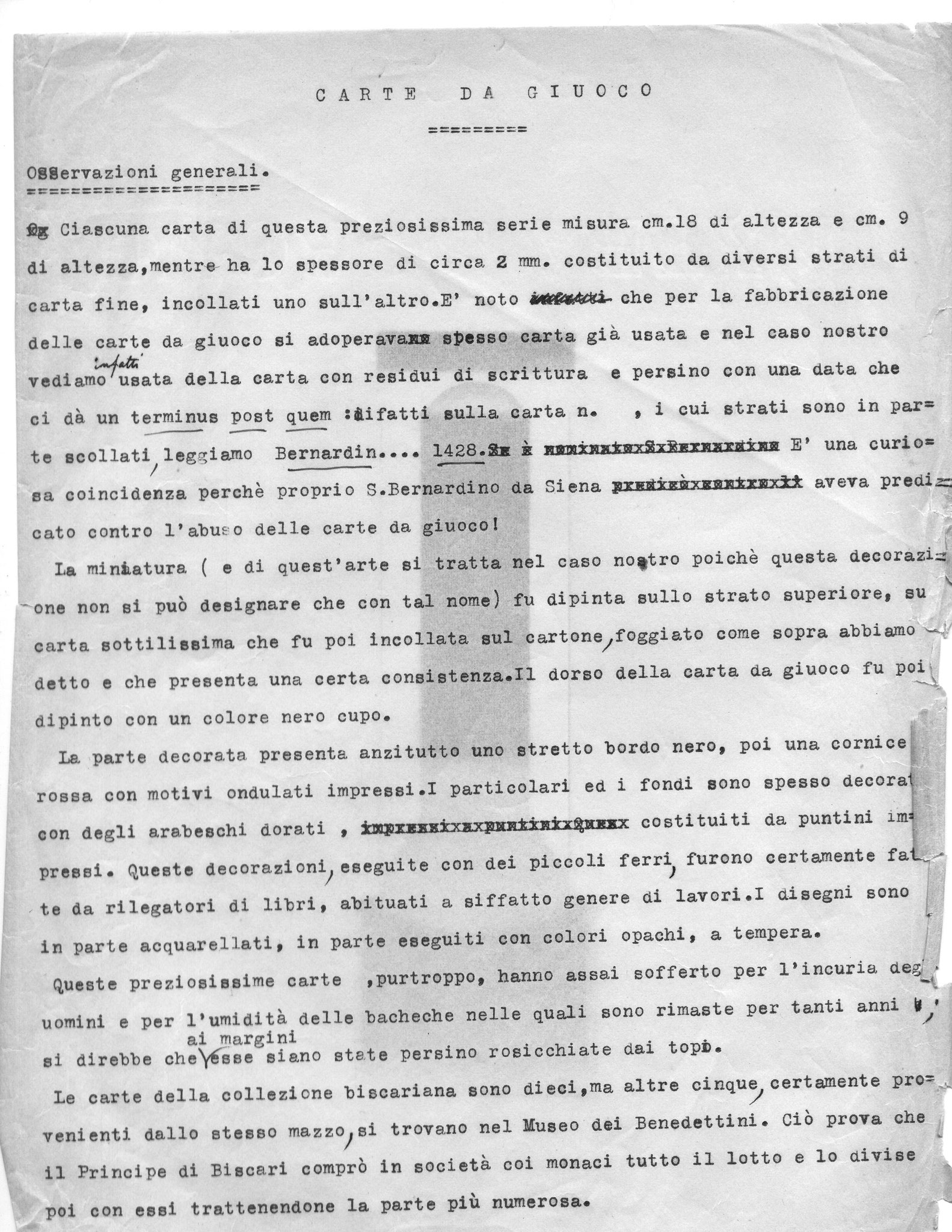

Documento "Carte da giuoco" di Ludvig Pollak [presso archivio del Museo Civico di Castello Ursino Catania]

Notes and Studies by Ludwig Pollak on the 15th-century playing cards from the Museo Biscari*

translated from the Italian by Emilia Maggio

PLAYING CARDS

General Remarks on the Catania playing cards

Each card in this rare series measures 18 cm in height and 9 cm in height [sic!], whilst it has a thickness of about 2 mm., made up of several layers of thin paper glued together. It is known that for the making of playing cards used paper was generally employed and in our case we can see, in fact, paper with traces of writing and even with a date which gives us a terminus post quem: in fact, on card no. [5], whose layers are partly detached, we can read Bernardin …. 1428. It is a curious coincidence, as it was St Bernardine of Siena who preached against the improper use of playing cards!

The illumination (as is the case here, since this decoration cannot be defined in any other way) was painted on the upper layer, on very thin paper subsequently glued onto rather heavy pasteboard, made as described above. The back of the playing card was then thickly painted in black.

The decorated side shows first of all a narrow black border, then a red frame with wavy punch-marked motifs. The details and backgrounds are often ornamented with golden arabesques made of engraved dots. These decorations, executed with small iron implements, must have been made by bookbinders used to such kind of work. The drawings are partly water-coloured, partly executed in tempera with opaque paints.

Sadly, these rare cards have much suffered through human carelessness, as well as the dampness of the showcases in which they have lain for many years; one would even say their margins have been nibbled by mice.

The cards in the Biscari collection are ten; five more, though, certainly coming from the same set, are in the Benedictines' Museum. This proves that the Prince of Biscari bought the whole lot in partnership with the monks and then shared it with them by keeping most of the cards.

Translator’s notes:

* In the original document this title is handwritten and the author’s first name is given in the Italian form, i.e., Ludovico. Pollak, who had moved to Rome in 1893, wrote in that year: "Roma, che vuol dire Italia, la mia alfa ed omega" (i.e., Rome, which means Italy, my alpha and omega).

Cf. ROSSINI, Orietta, Ludwig Pollak. La vita e le opere. http://www.museobarracco.it/sites/default/files/f_file/Biografia%20Pollak%20-%20O.Rossini.pdf p.1.

GENERAL REMARKS ON THE CATANIA PLAYING CARDS

[this looks like a revised second version of the above page, with several handwritten amendments]

Each card measures 18 cm in height and 9 cm in length, and is about 2 mm thick. The card itself consists of several layers of thin paper glued together. Generally speaking, the paper employed had previously been used for writing letters; on card no. [5] in this set, in fact, where the [upper] layers have partly peeled off the back, it is possible to read: Bernardin..1428. A strange coincidence, since St Bernardine of Siena himself preaches against the improper use of playing cards!

The illumination – as is the case here, for this decoration can be truly called miniature painting – was painted with colours on very thin paper. This sheet was then glued onto a heavier one (this too, as said above, made up of several layers), so as to acquire a certain strength. The back was then thickly painted in black.

The main side shows first a simple, narrow black border, then a red frame with wavy punch-marked motifs. The details and backgrounds are often ornamented with golden arabesques made of engraved dots. These decorations, executed with small iron implements, must have been made by bookbinders used to such kind of work. The drawings are partly water-coloured, partly executed in tempera with opaque paints.

Sadly, these rare cards have much suffered through human carelessness, as well the dampness of the showcases in which they have lain for many years; it even seems that their margins have been nibbled by mice.

The cards are ten in number. Five more from the same set are in the Benedictines' Museum. The Prince of Biscari must have bought the whole lot in partnership with the monks and then shared it with them. In the plates we show these rare antiques properly reproduced and in colour for the first time.

Description of the Biscari cards (nos. 1-10)

No. 1 Ace of Cups

The stem of the cup is held by a large right hand issuing from a sleeve. The base of the cup has a distinctive shape. On the edge of the basin, richly and thoroughly decorated with dotted punch-marked designs, sits a young naked angel with a full head of hair, long wings and a tiny necklace. Its right hand was on the corresponding piece of damaged paper. The left hand is stretched towards a dog also perched on the edge and sitting up on its hind legs.

The dog's skin has several white spots. On either side of the stem of the chalice, two heraldic herons with open beaks. The background is thickly decorated with vine scrolls and leaves. On the back there are traces of ink writing from the sheets of paper that were glued together.

Inv. 1979

Herons on German 15th-century cards. (Société pl. 86, 90)

also see below no. 9

cf. the little cupids on the French card "Les Amoureux" (Société, pl. 6)

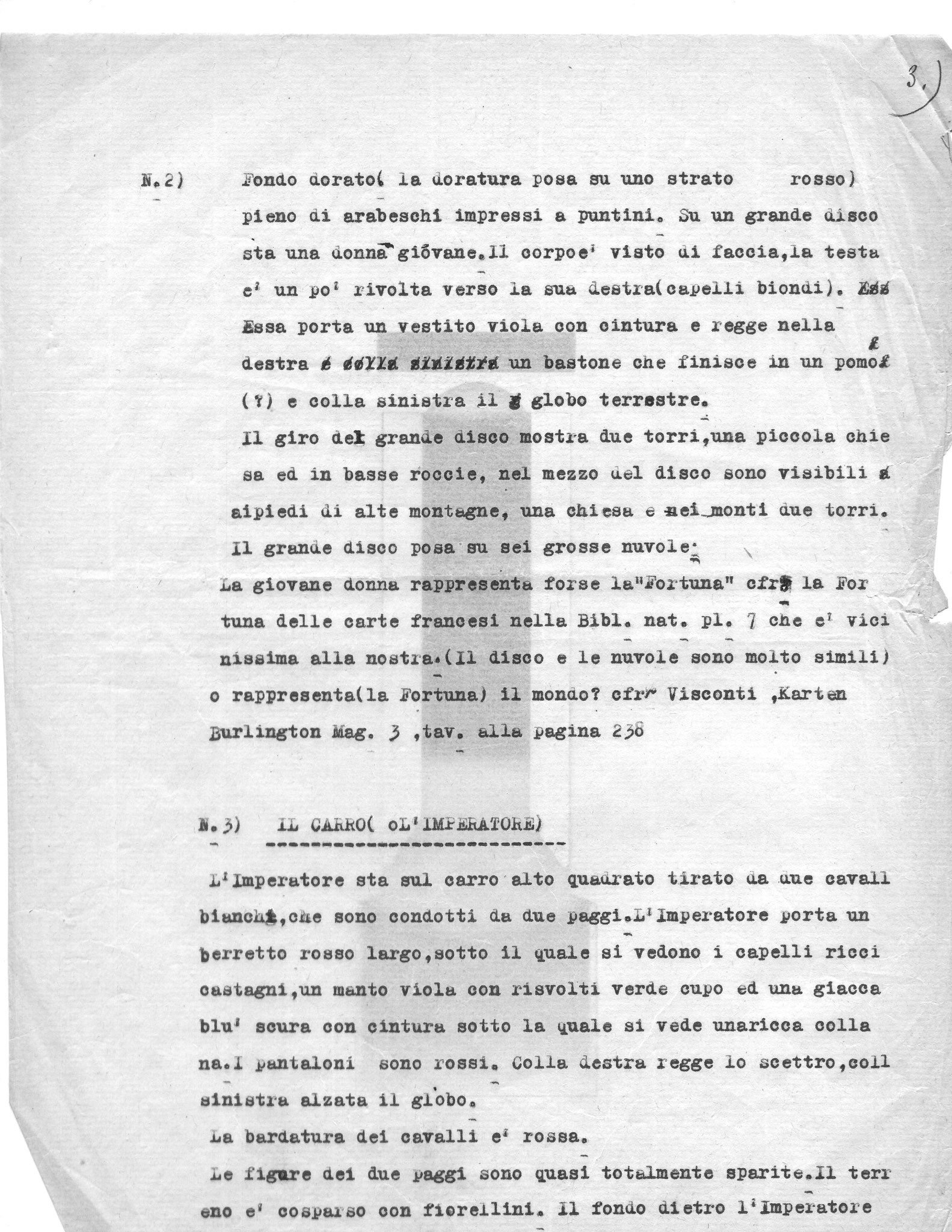

No. 2

Gilded background (the gilding lies on a red _____ layer) full of arabesques made of punch-marked dots. On a large disk stands a young woman. Her body is in front view, the head (blonde hair) is slightly turned to her right. She wears a purple dress with a belt and holds in her right hand a stick ending with a knob (?) and in her left hand the terrestrial globe.

The border of the large disk shows two towers, a small church and, below, some rocks; at the centre of the disk a church is visible at the foot of some high mountains, and two towers on the mountains. The large disc rests on six big clouds.

The young woman may represent "Fortune" – cf. Fortune in the French cards at the Bibliothèque Nationale, pl. 7, very close to this one (the disk and the clouds are very similar); or does (Fortune) represent the World? Cf. Visconti Karten, Burlington Magazine, 3, pl. on page 238.

No. 3 The Chariot (or the Emperor)

The Emperor stands on a tall square chariot drawn by two white horses led by two valets. The Emperor wears a large red beret, under which his brown curls can be seen; a purple cloak with dark green lining; and a dark blue jacket below with a belt, below which a sumptuous chain can be seen. The trousers are red. On his right hand he holds the sceptre, on his raised left hand the globe.

The horses' harnessing is red.

The figures of the two valets have almost completely disappeared. The ground is scattered with tiny flowers. The background behind the Emperor is gilded, as usual. In the Visconti cards, a woman [sits] on the chariot, probably Duchess Beatrice, see Burlington Magazine. Cf. the Chariot in the French cards, Société, pl. 13, and Baldini's Mars (Marte Willishire [sic!], pl. 8).

No. 4 The Page with Chalice

A young Page (profile facing right) bears a gilded and artistically decorated chalice. His hair is blond; his blue jacket is bordered with fur; his belt is gilded. A white cloak covers his shoulder, arm and left hand. His right sleeve is red; his right trouser-leg is red, the other is dark. The ground is blue with red flowers. The background is as usual.

In Baldini's cards (Société, pl. 22), the page holds a vase with the inscription FAMEIO with both hands. A similar vessel is carried by the page in the Venetian card game of 1491 (Société, pl. 81A).

Cf. the page in the cards at Museo Carrara in Bergamo, Burlington Magazine, III, [colour?] plate for page 247.

No. 5

On the back of a large stag facing right (a large band on its neck) sits a completely naked (blond haired) woman facing left who pours from a large cup, identical to those in the numerical cards, a liquid onto her own belly. The liquid spills onto the stag's body.

The green ground is scattered with tiny red flowers.

Allegory of Temperance (?). Cf. Burlington Magazine, p. 238.

I know no other examples of this iconography. On the back of the card there are traces of writing in ink, so among other [?] St Bernardine (of Siena) is mentioned, and the date 1428.

A very strange coincidence, as on the very sheet of paper used for making a playing card that very saint should be named who in 1423, in Bologna, preached with great success against card games (Willishire, ibid., p. 26).

The stag (alone) [is] only [found] on German15th-century playing cards (Société, pl. 86).

Cf. also a "Temperantia" [which] is completely different from [the one in] Baldini's cards (Société, pl. 54) and the French one sitting on a throne (Société, pl. 8).

"Temperanza" on the bell tower of Florence Cathedral (in the manner of Orcagna) and the winged one (Venturi, Storia, ill. 552, p. 669) in the Loggia dei Lanzi (Venturi: ibidem, fig. 592) are seated.

No. 6

In a rocky landscape stands an old Hermit, who holds a sand clock (its wooden frame is red) in his raised left hand. He is seen in profile and sports a very long white beard. On his head he wears a green hood with black spots. His red cloak is fastened on the right shoulder; his long robe is blue and its wide border is gilded; the narrow belt is also gilded; the feet are shod in red boots. The dark blue ground is scattered with red flowers. The back of the card carries traces of writing that can no longer be deciphered.

Cf. the hermit with the [missing word] in the Visconti (?) cards, Burlington Magazine.

On the upper left corner is written in brown ink by a later hand ______.

The Hermit is perhaps Fr Paphuntius of Alexandria, much venerated in Ferrara, or St Anthony Abbot.

Cf. the hermit in the French cards (black with a lantern), Société, pl. ___.

No. 7

Seven of (sabre) Swords

The swords cross each other. The hilts and ends are red. The gilded decorations are punch-marked, as usual. In the background, red clovers. On the back of the card, traces of writing.

No. 8

Nine of Straight Swords [i.e., Clubs]

The ________ and ends are painted in red and gold, the swords are dark red. Clovers on a plain background. The margins are very worn [literally: "gnawed"].

No. 9

Two of Coins

In the middle of the coins, two beardless human heads can be seen in frontal view. The eyes look towards their right. The disks are red with gilded ornamentation made of punch-marked dots. Between the two coins stands a heron. Its long neck is bent downwards. Its beak is open. In the background, clovers and scrolls.

Herons and storks on 15th-century German cards. Société, pl. 86, 90. See no. 1.

No. 10

Eight of Coins

Each coin shows a gilded flower formed by punch-marked dots, whose centre is indicated by a black circle (?). The plain background is decorated with clovers and scrolls, as usual.

Description of the Benedictines' cards

B. 1

King of Swords

Sits on a richly painted throne (the drawing imitates marquetry). On his head, a crown with six long spikes. Thick blond hair. Jacket _____, the sleeves have two frills.

Belt _____, the lower border of the jacket is trimmed with fur. In his right hand he holds a long sword (gilded hilt and pommel) turned upwards while his right hand rests on a shield. The shield is decorated with a ring like that of the Medici, in whose centre there is a ______ and four green leaves (the emblem of a matrimonial alliance?).

The trousers show the colour ____. The legs are crossed.

The background is gilded with arabesques formed by punch-marked dots. The gold ring has a pale brown faceted stone.

Cf. the very similar page in the French card at the Bibliothèque Nationale, pl. 3, and also the King of Swords in the Visconti set, Burlington Magazine, ill. on p. 238.

B. 2

Eight of Sabre Swords.

B. 3

Six of Straight Swords [i.e., Clubs].

B. 4

Ten of Chalices.

B. 5

Seven of Coins. (photo missing)

Quattrocento playing cards, worth being counted among the most beautiful antiques from the golden century of Italian art, were never studied enough; given their enormous importance, we would like to provide a complete list of them.

A LIST OF 15TH-CENTURY ITALIAN ILLUMINATED PLAYING CARDS AS KNOWN SO FAR

1) Visconti cards. 67 pieces. Size 19 x 9. Painted by Marziano di Tortona for Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan (1412-1447). They have always been with the [Visconti] family. Published by Count Parravicino in The Burlington Magazine (III, 1903, p.237 ff.). This set was originally paid 1500 gold ducats (about 80,000 lire today). Among the Italian cards, these are the earliest. Cf. D'Allemagne I, p.183 ff.

2) Giuseppe Brambilla cards. [1] 48 pieces. Size 17 x 7. Bought in Venice in the early 19th century. The background to the figures shows a lozenge pattern, that of the pips has floral motifs. The cards show Filippo Maria Visconti's colours and coat of arms; one coin card features a gold coin of the same prince. There is a quantity of remarkable Gothic motifs. These cards are from the same period as those at no. 1).

3) Colleoni cards. 61 pieces. Painted by Antonio di Cicognara in 1484 for Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, son of Francesco Sforza. Size 18 x 9 [cm]. Now they are divided as a) 35 cards belonged to Count Colleoni until 1903, when he sold them to J. P. Morgan; b) 26 cards kept at Bergamo's Accademia Carrara as a bequest of Count Baglioni.[2]

The famous illuminator Cicognara also painted another set of cards for two sisters of Cardinal Ascanio who were nuns at Cremona's Augustinian convent. These cards were lost when the convent was suppressed under Joseph II.

What the above decks (1, 2, 3) have in common is the gilded background of the figures and the silver background of the numeral cards.

4) Four cards in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London (Star, Knave of Coins, Death, the Fountain). 17 x 8.5 [cm], 2 mm thick. Colonel Croft Lyons bought them in Milan shortly before 1915 and they entered the Museum as his bequest. They are very likely to have been illuminated for the Colleoni family, for one of them (the Fountain Cupid) carries a shield with the Colleoni arms and the motto "nec metu". In style they are very different from the Catania set. The colours too are less subtle and the workmanship is coarser. In general, they are more similar to the Sforza cards at no. 3).

5) Four cards belonging to the "Worshipful company of makers of playing cards", London. They are much smaller than the others and measure 13.5 x 7 [cm]. In 1926 they were displayed at the Victoria & Albert Museum. The cards are: Knight, Ace of Swords, Fountain, Castle. Stylistically they are very close to the Colleoni cards (no. 3).

6) The Museo Correr, Venice, owns four cards which I am reproducing with the Director's kind permission. The Director has also provided me with photographs made by Cavalier Pietro Fiorentini. The cards were bequeathed to the Museum by its founder Teodoro Correr. They measure 17.6 x 9.3 [cm]. The backgrounds are decorated with blue scrolls and small gilded discs with great profusion of dots. The cards are the following: a) Ace of Swords (?). A large sword with gilded handle enfiling a large lilied crown, also gilded. A red heart is skewered on the tip of the sword. b) Two of Clubs. The handles and ends are gilded. One club is blue, the other is red. d) [sic!] Four of Coins. The discs are gilded with dots forming punch-marked rosettes arranged to form a circle, and a larger rose in the middle. The back is undecorated and of an ivory-yellow colour. Cf. Merlin, "Origine des cartes à jouer", 1869, pl. 8, 9. These cards are completely different from the Catania ones.

7) 16 cards originally in the Figdor Collection, Vienna. Sold at auction in Lucerne on June 15th 1932 (Katalog Gilhofer u. Ranschburg, p. 127, no. 612 Taf. 49). They come from the collection of Baron Gerôme [sic!] Pichon, who bought them from Victor Gay. Size: 13.9 x 7.8. See Allemagne I, p. 184 ff. and II, plate[s?] on p. 12 and p. 38. Four were published by d’Allemagne in "Rivista del Collegio Araldico", 1906, p. 270 ff. (a) Queen of Cups, Figdor Sale, plate 49; b) Knave of Swords, d) [sic!] Knight of Swords, Figdor Sale, plate 49).

The gilded punch-marked background is similar to the Catania cards, but these cards are smaller, very different in style and much later (end of the 15th century).

8) Count Cicognara owned 23. Each measured 19 x 9 [cm] and was four times larger than the usual cards. Later, they came to be owned by the Tress [?] frères, Paris. Their present whereabouts are unknown. (Cf. Cicognara, Memorie, etc. p. 160. Merlin, Origine des cartes à jouer, p. 90).

When talking about 15th-century Italian playing cards, these are associated with the so-called Mantegna Tarot. Yet, the name of this most important master is wrongly connected with them. These engravings are the work of Florentine goldsmith and engraver Baccio Baldini, who designed them in Florence around 1470. Then they were engraved in Venice, which explains the Venetian dialect in the inscriptions that are visible on them [3].

The playing cards that came from the Orient had been known in Europe from the year 1369;[4] they were introduced into Viterbo in 1379. The oldest to have come down to us are the famous 17 hand-painted French cards from the Bibliothèque Nationale (no. 5634), called of Charles VI (1380-1422). They are assumed to have been painted between 1390 and 1393, but an accurate examination of the originals suggests to me the beginning of the Quattrocento, hence quite close to the Visconti cards. They have a strong French look and have nothing to do with the Italian ones. The first colour publication was made by the Société des Bibliophiles français, Paris, 1844, under the title "Jeux de cartes Taroc et des cartes numerales, etc.".

Among the Italian cards that have come down to us, the oldest are certainly the Visconti ones (no.1). They are like the Brambilla (no.2) and the Colleoni cards (no.3) and certainly from Lombardy.

If we wonder which Italian region should the Catania cards be assigned to, we should first of all exclude Sicily, despite the fact that we know (Cicognara, p. 129) that, as early as 1450, a large quantity of playing-cards were imported into Sicily from Germany in exchange for colonial goods (p.8)[5]. The Catania cards, however, are doubtlessly Italian and, if we look at their style, certainly from Northern Italy, though from neither Lombardy nor Venice. A stylistic comparison with the Lombard and Venetian cards (nos.1-3) would absolutely exclude this.

One might perhaps think of Florence. Among the Benedictines’ cards (B1) on the shield held by the King an emblem is visible: a golden ring with a faceted diamond. Inside the ring stands a red feather with two green leaves at either side: [6] it is therefore the i[mpresa?]. Joined together with the impresa of the Gonzaga, Cosimo the Elder did, as the founder of the [Medici] dynasty, use the ring as a personal emblem. Should we therefore think of a Florentine origin for these cards? I don’t think so. As we have seen in the Visconti and Brambilla sets, Italian Quattrocento cards often display crests. The same happens, later, with the Este coat of arms (cf. Campori, ibidem). These « imprese » or crests refer to the people who ordered the cards and have nothing to do with their place of production.

We do know that a set of illuminated cards was an extremely precious gift and often made a wedding present (Cicognara, ibidem, p.148 ff.). The Catania cards might as well have been ordered as a present by Cosimo the Elder (1389-1464) for the wedding of a member of his house with a Gonzaga, not from a Florentine painter but from a Northern Italian master.

A stylistic comparison of card no. 5 (the Stag) takes us to Verona, as it shows an evident Pisanello influence, while a number of other reasons take us to Ferrara and others to Mantua. The same thing applies to our no. 6 (the Hermit): a drawing from the Albertina in the manner of Pisanello (van Marle, "The Italian schools of painting", VIII, p. 119, fig. 68) is very similar; even more similar is the St Anthony Abbot in Pisanello’s painting at London’s National Gallery (van Marle, ibidem, fig. 65), dated about 1440.

Certain Ferrarese influences are also evident. Thus, the landscape in our card no. 2 [the World] finds a very eloquent comparison in a miniature by Reginaldus Pisanus de Monopoli di Bari, whose artistic dependence on the Ferrarese school has been highlighted by Hermann.[7]

It is within the Ferrara-Mantua-Verona triangle that we must place the anonymous master of the Catania cards, which would be dated around 1450.

Literature on playing cards in general is vast; not all books, however, deal with their artistic side, which is the most important thing.

The main works are:

Henri René d'Allemagne, Les cartes à jouer du XIV au XX siècle, II vol. Paris, 1906 (a masterpiece).

Merlin, R., Origine des cartes à jouer. Recherches nouvelles sur les Naibis les Tarots et sur les autres espèces des cartes. Paris, 1869.

Jeux de cartes Tarots et des cartes numerales du XIV au XVIII siècles [représentés en] cent planches d'apres del originaux publiés par la Société des Bibliophiles Français. Paris, Imprimerie des Crapelet 1844 (very rare!).

Hughes Willshire, A descriptive catalogue of playing and other cards in the British Museum 1876.

Samuel W. Singer, Researches into the history of playing cards, London, 1816.

As to Italian cards in particular: cf. Cicognara, Memorie spettanti alla storia della calcografia, Prato, 1834.

Venturi, Rivista storica di Torino.

Campori, Le carte da giuoco dipinte per gli Estensi nel sec. XV, Mantova, 1875.

Zdekauer, Il giuoco in Italia nell'Archivio stor. ital. XVII, 1886.

Zdekauer, Archivio veneto XXVII, p. 132 ff.

A. Lenzi, Bibliografia italiana dei [giuochi di] carte. Firenze, 1892.

Translator's note:

There are two footnotes which I was unable to place:

Cf. J. Gelli, Divise motti e imprese p. 437 no. 1555.

In Graz Cathedral there are some interesting reliquaries coming from Mantua and evidently based on drawings executed by Mantegna between 1450 and 1460, the Gonzaga impresa appears more than once. Cf. Coudenohove-Erthal. Die Reliquienschreine des Grazer Domes, Taf. 18.

[1] For the Brambilla cards the antiquarian Baslini offered 3,000 francs in 1903. For the 26 Colleoni cards (our no. 3b), Count Roncalli of Bergamo was offered 5,000 lire. The cards were then given by Countess Colleoni to Count Baglioni in exchange for a painting by Fra' Galgario.

[2] The stylistic distinction is incorrect. All these cards are by one and the same hand.

[3] Also cf. Hermanin, "La vita nelle stampe", p. 27, ff.

[4] The oldest illustration of card players is found in a manuscript in the British Museum (no. 12228) "Le Roman du Roi Meliadus de Lennoys par Helie de Borron". The relative illumination on folio 313 is published by Singer, Researches, p. 68, and in the Art Journal 1859, p. 87. The date is around 1350. Cf. also H. Willshire, A descriptive catalogue of playing and other cards in the British Museum, 1876, p. 14.

[5] We also know that in 1427 some German masters in Bologna designed playing cards, cf. Burchhardt, Kultur der Renaissance, XI ed. II, Excurs. p. __ and there were so many cards imported into Venice from abroad that Venice saw its own production under threat.

[6] The Rucellai too had the diamond and feathers.

[7] Jahrbuch des Kaiserhauses XIX (1898) p. 147 ff., 201 f.

BERGAMO-NEW YORK Triunfi: UPDATE AND INSIGHT

di Ronald Decker

The author is deeply grateful to Kristopher Rekers for the illustrative slides. They were prepared for the IPCS convention and are also available on the internet:

Orientation

When the Tarot originated, in fifteenth-century Italy, the deck’s special set of allegorical images were called triumphi (in Latin). They served as trumps. (The English word “trumps” in fact descends from triumphi.) The Bergamo-New York deck would seem to have been a conventional Tarot. Amply represented are trumps and four suits, the latter having the usual hierarchies and suit-signs. Two trumps – the Devil and the Tower – are absent. Among the suits, only the Three of Swords and the Knight of Coins are lacking. Accidents of history have divided the deck between two locations, the Accademia Carrara (Bergamo) and the Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum (New York).1

The deck was produced by illuminators, i.e. miniaturists. The cards, as paintings, are small; but, as playing-cards, they are large, measuring 175 x 87 mm (fig. 1). The substrate is pressed cardboard. The backs of the cards are painted red. The front sides are lavishly painted: prettified figures pose against gilded backgrounds.2 Gold and silver cover the majority of costumes. Those layers are inscribed with heraldic devices, many belonging to the rulers of Milan, specifically the Visconti dukes, followed by Visconti-Sforza dukes. The latter inherited the Visconti heraldry and added their own.

We must make a critical distinction. I will designate the majority of these cards as “primary” cards. They are rendered in the International Gothic style. Quite different are six “secondary” cards: Fortitude, Temperance, Star, Moon, Sun, World (fig. 2). These are rendered in a revived classicism that was typical of Renaissance art. They are compatible with the primary cards in having essentially the same golden backdrops and of course are of the same dimensions. But the secondary cards are on thinner cardboard. Moreover, the costumes here are classical and do not have the look of heavy fabrics like those suggested by the silver and gold surfaces. Three of the Renaissance cards are in Bergamo (fig. 3). Three are in New York (fig. 4).

I will limit the scope of this presentation by attending to the relevant books published by early IPCS members: Gertrude Moakley, Michael Dummett, Stuart Kaplan. They differ in their opinions about the artists responsible for the deck. The correct attributions are the major concerns of this presentation.

Moakley’s Contributions

In Gertrude Moakley’s day, art historians had reached a consensus – correct or not – that Bonifacio Bembo, an artist working in Cremona, painted the primary cards. Heraldic emblems in those cards indicate patronage by Francesco Visconti-Sforza, who became the fourth duke of Milan in 1450. The primary cards were painted at about that time. Moakley accordingly titled her book The Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo for the Visconti-Sforza Family (1966).

Moakley also wrote about a certain “mix-up.” When the Bergamo-New York triumphi were catalogued in both the Accademia and the Pierpont Morgan, the archivists listed the artist as Antonio Cicognara (fl. 1500). He was active in Cremona and allegedly painted a Tarot for a Sforza patron.3 In fact, the “substantiating” report has long been recognized as a hoax.4 We have no real evidence that Antonio painted any cards whatsoever. This warning has been overlooked by several historians and archivists. Nevertheless, Antonio has lost ground. No longer is he regarded as the principal painter of the entire deck, but a few authors persistently attach his name to the secondary cards.5 Moakley, as well as Dummett, tried to correct this misattribution.

Dummett’s Contributions

In 1980, when Michael Dummett published his authoritative book, The Game of Tarot, he agreed with Gertrude Moakley that our primary cards were by Bonifacio Bembo.

In 1981, Giuliana Algeri issued her art history study, Gli Zavattari, about a family of artists who worked in Lombardy, ca 1440-1480. She revived an old belief that the dominant style in our deck is comparable to frescoes painted by the Zavattari family. She credited our primary cards to Francesco Zavattari.6 She noted that six trumps were of a later style, but she did not otherwise specify their date or speculate about their creator.

When Dummett wrote The Visconti-Sforza Tarot Cards (1986), he followed Giuliana Algeri in attributing the primary triumphi to Francesco Zavattari. Similarly, Dummett refrained from naming the maker of the secondary triumphi. Dummett continued his campaign to banish Antonio Cicognara from the literature about playing-cards.

Dummett must have decided that he could best depose Antonio Cicognara by supplying a more convincing nominee for the secondary cards. Those later cards have been described as Ferrarese.7 Ferrarese painting was said to have influenced Benedetto Bembo, one of Bonifacio’s brothers. Therefore, in 2007, Dummett published an article that credited the secondary cards to Benedetto.8

Kaplan’s Contributions

Stuart Kaplan’s multi-volume Encyclopedia of Tarot has disseminated information about the history, design and symbolism of the cards, ranging from the Renaissance to the present. 9 Kaplan, a publisher of cards, has issued reproductions of the Bergamo-New York triumphi.10 The most recent printing is accompanied by a booklet, The Visconti-Sforza Tarocchi Deck. Kaplan perhaps relies on Dummett’s nomination of Benedetto Bembo as the secondary artist:

It is believed that [Bonifacio] Bembo did not paint all the cards, but was helped by his brothers. This would explain why six of the Visconti-Sforza cards have a different style (Strength, Temperance, The Star, The Moon, The Sun and The World): they might have been painted at the same time, though by a different hand.11

Decker’s Contributions

Modification: a comment on the primary cards

In 1988, Mikl s Boskovitz, an art historian, made a discovery that improves the attribution of the primary cards in the Bergamo-New York triumphi.12 He was familiar with a certain manuscript called The Story of Lancelot of the Lake.13 It contains no fewer than 289 pen-and-ink illustrations. They would have been completed ca 1450. Boskovitz recognized a stylistic match between the Lancelot illustrations and a sketch on the cover of a Cremonese ledger, specifically the record book for a charitable organization, the Consortium of St Omobono. This drawing is dated to 1450 and is documented as the work of Ambrogio Bembo.14 Ambrogio was yet another brother of Bonifacio. They collaborated closely in the 1440s and thereafter. Judging from the St Omobono sketch, the Lancelot illustrations are also by Ambrogio. The Lancelot characters – in their physiques, poses and costumes – are closely akin to those in our primary cards. Some experts reasonably assume that Ambrogio was responsible for most of our triumphi.15

In my opinion, Boskovitz’s discovery, while brilliant, does not require us to shun Bonifacio Bembo or even Benedetto when we try to sort out our card-makers. All the brothers worked in very similar styles. I think that the best we can do at present is to declare that our primary cards are by “the Bembo workshop”. Further research may allow us to distinguish the handiwork of each brother.

Objections: two comments on the secondary cards

(1) The secondary cards need not have been part of the original project (pace Kaplan). On the contrary, a decidedly different date is strongly suggested by the disparity in style, the Gothic majority of cards versus the Renaissance subset of six cards. We also recall that the card stock of the Gothic cards is heavier than the Renaissance cards. This probably indicates that the secondary artist was employed in an entirely different workshop. Furthermore, he may actually have had a different patron, for the six later cards lack the Visconti-Sforza emblems so abundant in the Bembo cards.

(2) If we were to accept Dummett’s attribution of the secondary triumphi to Benedetto Bembo, we would need to explain why that artist so radically departed from the style and workmanship of the Bembo studio. The main motive for distinguishing six cards from the majority is precisely the contrast of styles. Benedetto’s departure from the norm would be decidedly odd: he more probably would have tried to supply cards stylistically integrated with the primary cards. And he would have had no difficulty, for he was fully indoctrinated in the family style. Indeed, he probably would have had access to his family’s pattern books with models to imitate. The secondary cards, I insist, are from some other source, one with a different aesthetic.

Secondary Repairs and Added Details

First, I refer to the areas at the feet of the principal figures where green grass is depicted (fig. 5). All the grass in the secondary cards is intact. I observe that the secondary artist repaired many of the primary cards (at least 13 court cards and 11 trumps and the Fool). Among the primary cards, the pigment for the grass badly failed, and the secondary artist applied a new layer. However, the deeper strata did not provide an adequate ground for the repair. That too has eroded over time. Within the rendering of grass, we can see that the secondary plants are more refined than those typical of the Bembo workshop. Among our cards, the Bembo plant-life survives only in the upper zone of the Justice card. The primary cards, as previously noted, were painted ca 1450. We can allow a generation or so for the deterioration of the original greenery. This again brings us forward at least to the 1470s.

The later artist also added some of his special enhancements. Wherever hills and cliffs appear, not only in the secondary cards but in many of the Bembo cards, those landscape details are touches by the later artist. For instance (fig. 6), in the Fool card (from the Bembo studio), the hills are obvious additions, extending above the original horizon and intruding upon the original gilding with its incised pattern. As for the characteristic cliff edge, it is prominent in four of the secondary cards and has been inserted into several primary cards. Who was the artist who regularly decorated his landscapes with rolling hills and rocky cliffs?

The Secondary Artist

Credit is long overdue. My nominee is Cristoforo de Predis (1440-1486). We have an abundance of images from his career as an illuminator. In four manuscripts, his handiwork is beyond doubt, for he has carefully inscribed his name.16 My case for Cristoforo is based entirely on stylistic analysis. Here I will depend mostly on a well-known manuscript called De Sphaera.17 In the first of its illuminations, we find Visconti-Sforza coats of arms. The manuscript is most often dated to about 1470. If this is correct, the patron was probably Duke Francesco’s son and successor, Galeazzo Visconti-Sforza (1444-1476). Galeazzo and his mother were enthusiastic about astrology. De Sphaera is an astrological manual. It depicts the planetary deities. For each of them, the artist also illustrates a traditional theme, “the children of the planets”. These are not baby deities but are adult humans with qualities supposedly instilled by the gods or goddesses who dominate a given horoscope.

The following comparisons are offered as evidence that Cristoforo painted the six classical trumps in the Bergamo-New York triumphi.

Trump traits ____ Comparison with de Predis manuscripts

Landscapes with scattered pebbles De Sphaera title page (fig. 7)

Rolling hills De Sphaera (detail) Children of Mars (fig. 8)

Foreground cliffs De Sphaera Children of the Moon (fig. 9)

Passive faces (female) De Sphaera (detail) Venus (fig. 10)

Stressed faces (male) De Sphaera (detail) Mercury (fig. 11)

Long fair hair, high foreheads De Sphaera (detail) Luna (fig. 12)

Clothing with vertical folds De Sphaera (detail) Virgo (fig. 13)

Clothing in magenta and dark blue De Sphaera Venus (fig. 14)

Male nudes with muscles De Sphaera Mercury (fig. 15)

Numerous putti Libro d’Ore Marriage of the Virgin (fig. 16)

Many more examples of these traits can be found among Cristoforo’s illuminations. None of the above comparisons, when standing alone, would uphold him as the source of the relevant trumps. However, when we take these comparisons as a group, the case seems convincing. Cristoforo de Predis was the illuminator who completed the Bergamo-New York triumphi.

Addendum:

Shephard’s Contributions

John Shephard was another member of the IPCS and an author who wrote about the Bergamo-New York triumphi. He did not attempt to identify the card-makers. He was interested in the esoteric symbolism that he perceived in the cards. In his iconographical study, The Tarot Trumps, Cosmos in Miniature (1985), Shephard helpfully explained the presence of the six idiosyncratic cards. They are not “replacement” cards, as is generally supposed. Shephard writes:

The most likely explanation seems to be that there was some kind of reorganization of the Visconti-Sforza pack and that the purpose of the new cards was to convert it from an older form…into the new kind of sequence which eventually came to be accepted as standard.18

Significance of Cristoforo’s trumps

I would slightly revise Shephard’s statement: perhaps the new sequence of trumps had already become standard, and the secondary artist was commissioned to bring the original deck up to date. I happen to disagree with the particulars of Shephard’s theory of Tarot symbolism, but I have long believed that the trump symbols indeed have esoteric meanings. These, I think, combine moralistic and cosmic (astrological) programs.19 I have published my iconographical theory elsewhere.20

I can briefly observe that Cristoforo’s cards form a nicely unified set, not random as they would be if they were needed merely to reinstate cards lost by accident. We find my two iconographical themes, moralistic and cosmic (fig. 17). The Bembo workshop gives us a version of Justice (moralistic). The card’s upper corners display two solar emblems (cosmic). Cristoforo gives us the Virtue of Temperance (moralistic) with a gown bestrewn with stars (cosmic). Cristoforo extends the cosmic theme through whole cards: Star, Moon, Sun, World. Furthermore, if we can judge by the trump sequence that now prevails, Cristoforo’s allegories nearly constitute a connected series: (11) Fortitude… (14) Temperance… (17) Star, (18) Moon, (19) Sun… (21) World.

Possibly, then, Cristoforo provides important evidence of the final stage in the Tarot’s development during the fifteenth century. We can appreciate his cards for their beauty, their symbolism and their information.

______________________________________________________________________________

Notes

1. The Accademia item is catalogued as 06AC00889. The Pierpont Morgan item is catalogued as M630. All of the surviving cards were once in the collection of the Colleoni family in Bergamo. In the late 1800s, 26 of the cards were exchanged for artifacts belonging to a family friend, Count Francesco Baglioni. He died in 1900 and bequeathed those cards to the Accademia Carrara, Bergamo, where they still reside. The Colleoni family apparently sold 35 companion cards. Hamburger Frères, an art dealership in Paris, retailed this set to the famous financier, John Pierpont Morgan in 1911. His purchases are in the Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Thirteen numeral cards remained with the Colleoni family, who recently loaned them long-term to the Accademia.

2. The imagery is executed with opaque tempera. Some of the gold backgrounds have eroded to reveal a primer coat of bole (red clay). Wherever the numeral cards have touches of gold, those areas are incised. The gold backgrounds for the figure cards are incised with lines and dots, arranged in a lattice that contains a repeating pattern of suns. In all the numeral cards, the backgrounds are white but with floral tracery. Several numeral cards, those possessing fewer suit-signs and more space, tend to have scrolls that bear Visconti-Sforza mottoes, amor mio (“my love”) and a bon droit (“with good right”).

3. Count Leopoldo Cicognara published his Memorie spettanti la storia della calcografia (Prato: 1831). Cicognara was an art connoisseur and a statesman (as Prime Minister of the Cisalpine Republic). In his book, he says that his ancestor, Antonio Cicognara, painted a Tarot deck for Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, Duke Francesco’s son. Unfortunately, this story did not derive from the count’s own knowledge but was concocted by a dealer in antique documents. The document in question actually exists but has been found to lack the entry about Antonio as a maker of cards. See Moakley (1966), p. 27.

4. The hoaxer was suspected by Francesco Novati as early as 1880 and was denounced by Ugo Gualazzini in 1931. See Moakley (1966) pp. 27-28.

5. Sandrina Bandera Bistoletti upholds Cicognara as our secondary artist. See Sandrina Bandera and Marco Tanzi, “Quelle carte de triumphi che se fanno a Cremona”, I tarocchi dei Bembo dal cuore del Ducato di Milano alle corti della valle del Po [entry by S. Bandera in a catalogue of a Pinacoteca di Brera exhibition, curated by S. Bandera and M. Tanzi], (Milan: 2013), p. 52.

6. Giuliana Algeri, Gli Zavattari, Una famiglia di pittori e la cultura tardogotica in Lombardia, (Rome: 1981), pp. 59-90.

7. Robert Klein, “Les Tarots Illuminés du XVe Siècle”, L’Oeil, No. 145, January 1967, pp. 11-17, 51-52.

8. Michael Dummett, “Six XV-Century Tarot Cards: Who Painted Them?”, Artibus et Historiae, No. 56 (xxviii), 2007, pp. 15-26.

9. Kaplan’s Encyclopedia, Volume I (New York: 1978), summarizes the case for Bonifacio Bembo’s authorship of the primary cards among our triumphi (p. 106). In Volume II (New York: 1986), Kaplan provides data about Bonifacio and illustrates some of the art then attributed to the artist (pp. 120-140).

10. Grafica Gutenberg, a press in Bergamo, first issued the deck with the missing cards represented by line drawings. Kaplan collaborated with Grafica Gutenberg in 1975 to produce another version with different substitutes painted by an uncredited artist [see Kaplan, Volume I (1978), p. 285]. For the current deck, Kaplan commissioned Luigi Scapini, an Italian designer, to paint the four missing cards.

11. Stuart R. Kaplan, The Visconti-Sforza Tarocchi Deck (Stamford, CT: revised third edition 2016), p. 16.

12. Miklós Boskovitz, “Arte Lombarda del primo Quattrocento: un reisame; Bottega dei Bembo (Ambrogio Bembo?)”, Arte in Lombardia tra Gotico e Rinascimento [catalogue for exhibition curated by Boskovitz], (Milan: 1988), pp. 176-177.

13. The manuscript has no title page. The artifact is Codice palatino 556, Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence.

14. The artifact is Sant’Omobono e devoti, reg. 381, Archivo di Stato, Cremona.

15. Marco Tanzi, Arcigoticissimo Bembo (Milan: 2011), p. 47. Tanzi, although the prominent biographer of Bonifacio Bembo, unhesitatingly states his opinion that our triumphi are by Ambrogio. Card historians may be surprised to learn that Prof Tanzi transfers to Ambrogio two other Bembo Tarots (one in Milan’s Pinacoteca di Brera, and one in Yale University’s Cary Collection). I agree with these opinions – adding the caveat that some details are almost certainly by other members of the Bembo workshop.

16. The four signed manuscripts are: (1) two clippings, the larger including a depiction of Duke Galeazzo Sforza, Wallace Collection, London, (2) Missale [Missal], Sacro Monte,Varese, (3) Offizio della Beata Vergine [Prayer Book of the Blessed Virgin] or Libro d’Ore Borromeo [Borromeo Book of Hours], Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan, (4) Vite dei Santi [Lives of the Saints] or Legendario [Legendary], Biblioteca Reale, Turin. I owe these citations to Fernanda Wittgens, Cristoforo de Predis (Florence: 1935), p. 3.

17. The item is catalogued as α.x.2.14 = lat. 209, Biblioteca Estense, University of Modena.

18. John Shephard, The Tarot Trumps, Cosmos in Miniature (Wellingborough: 1985), pp. 29, 39. Shephard preserved Moakley’s theory that the Tarot’s symbolism ultimately derived, at least partially, from Petrarch’s poem, I Trionfi. However, Shephard thought that the Bergamo-New York triumphi were modified by the secondary cards and became ancestral to the so-called Tarot de Marseille. For my part, I now dismiss the Petrarchan connection, and I believe that the “Marseilles” version was already in existence (as a Milanese invention) when Cristoforo de Predis completed the Bergamo-New York triumphi.

19. I first presented this idea in two illustrated lectures at the 1977 IPCS convention at Hove, England.

20. Ronald Decker, The Esoteric Tarot: Ancient Sources Rediscovered in Hermeticism and Cabala (Wheaton, IL: 2013).

Bibliography

Algeri, Giuliana. Gli Zavattari, Una famiglia di pittori e la cultura tardogotica in Lombardia, Rome: De Luca, 1981.

Bandera, Sandrina, and Marco Tanzi. “Quelle carte de triumphi che se fanno a Cremona”, I tarocchi dei Bembo dal cuore del Ducato di Milano alle corti della valle del Po, Milan: Skira, 2013.

Boskovitz, Miklós. “Arte Lombarda del primo Quattrocento: un reisame; Bottega dei Bembo (Ambrogio Bembo?)”, Arte in Lombardia tra Gotico e Rinascimento, Milan: exhibition catalogue, 1988, pp. 176-177.

Decker, Ronald. The Esoteric Tarot: Ancient Sources Rediscovered in Hermeticism and Cabala (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 2013).

Dummett, Michael. The Game of Tarot, London: Duckworth, 1980.

Dummett, Michael. The Visconti-Sforza Tarot Cards, New York: Braziller, 1986.

Dummett, Michael. “Six XV-Century Tarot Cards: Who Painted Them?”, Artibus et Historiae, No. 56 (xxviii), 2007, pp. 15-26.

Kaplan, Stuart R. Encyclopedia of Tarot, Vol. I, New York: U. S. Games Systems, 1978.

Kaplan, Stuart R. Encyclopedia of Tarot, Vol. II, New York: U. S. Games Systems, 1986.

Klein, Robert. “Les Tarots Illuminés du XVe Siècle”, L’Oeil, No. 145, January 1967, pp. 11-17, 51-52.

Milano, Ernesto. Commentario al codice De Sphaera (α.x.2.14 = lat. 209) della Biblioteca Estense di Modena, facsimile edition, Modena: Il Bulino, 1995.

Moakley, Gertrude. The Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo for the Visconti-Sforza Family, New York: New York Public Library, 1966.

Shephard, John. The Tarot Trumps, Cosmos in Miniature: the Structure and Symbolism of the Twenty-two Tarot Trump Cards, Wellingborough: Aquarian Press, 1985.

Tanzi, Marco. Arcigoticissimo Bembo, Milan: Officina Libraria, 2011.

Wittgens, Fernanda. “Cristoforo de Predis”, La Bibliofilia, XXXVI, 1934, pp. 341-370.

Wittgens, Fernanda. Cristoforo de Predis, monograph XIII, Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1935.

TAROCCHI RINASCIMENTALI TRA MILANO E FERRARA

di Cristina Dorsini

Nel periodo dei Visconti e degli Sforza la città di Milano fu un crocevia politico e culturale d’Italia. Milano era una capitale ricca e sontuosa e forse, dopo Parigi, la città più grande e più popolosa d’Europa, al centro delle strade che dalla Francia andavano verso Venezia e dal Nord Europa scendevano nell’Urbe, governata dal Papa.

Da qui le pretese mecenatistiche dei due casati, che fecero di Milano un centro nevralgico dell’arte italiana. Con il passaggio di potere tra i Visconti e gli Sforza, a metà del XV secolo, si compì anche la transizione tra la stagione del gotico internazionale lombardo e l'apertura verso il nuovo mondo umanistico.

Nella prima metà del XV secolo a Milano e in Lombardia ebbe maggior seguito lo stile gotico internazionale, tanto che in Europa l'espressione ouvrage de Lombardie era sinonimo di fattura preziosa, riferendosi soprattutto a quelle miniature e oreficerie che erano espressione di uno squisito gusto cortese, elitario e raffinato. Il tardo gotico si caratterizzò per amore del lusso, preziosità di oggetti ed eleganza formale, con abbondanza di oro, materiali pregiati, colori luminosi e smalti. Altre caratteristiche erano l’esaltazione cortese e rinascimentale della figura femminile e una grande attenzione al realismo minuto delle rappresentazioni. L’opera più importante in Lombardia fu l’inizio del Duomo di Milano, per il quale il Visconti richiamò artisti francesi e tedeschi, che costruirono l’edificio più vicino al gotico transalpino d’Italia. Tale affluire di artefici da diversi luoghi, provocò un profondo cambiamento dello stile della scultura lombarda.

Nella pittura, l’Italia settentrionale aveva una certa unità stilistica, rappresentazioni realistiche che poi caratterizzanno la scuola lombarda, fondata sulla bellezza e il fascino naturale del modello di natura, veri portatori della “grazia”. L’artista più rappresentativo dell’epoca fu Michelino da Besozzo, miniatore, pittore e architetto: rinnovò lo stile trecentesco a favore di una maggiore fluidità, con colori tenui e preziosi; all’appiattimento spaziale rispose con un decorativismo ritmico sottolineato da raffinate cornici di fiori, sapientemente riprodotti dal vero. Attivo a Milano presso i Visconti e i Borromeo, lavorò anche per la fabbrica del Duomo, benché non ne sia rimasta traccia, e influenzò fortemente i pittori lombardi fino alla seconda metà del XV secolo. Il XIV e XV secolo furono dunque tra i più straordinari della storia milanese e lombarda, celebrati dalla storiografia e fissati nella memoria comune come una sorta di età dell’oro, il primo momento di compiuta realizzazione di una civiltà di corte dal respiro europeo.

L’altra importante corte italiana fu quella degli Este a Ferrara, una delle più vitali dell'Italia centro-settentrionale fin dalla fine del XIV secolo: qui si formò un ambiente originale e unico, che perpetuò le tradizioni cavalleresche di origine medievale, unendole e interpretandole in modo innovativo, con i nuovi gusti e le nuove tendenze umanistiche e rinascimentali.

In un’epoca in cui le Signorie affidavano all’arte la promozione del proprio territorio e del loro buon governo, i regnanti di Ferrara ebbero grande attenzione per le arti e le lettere. Già dall’inizio del Quattrocento Niccolò III (al potere 1393-1441) si era dimostrato abile mecenate, impiegando artisti del calibro di Pisanello, ma soprattutto accogliendo a Ferrara il classicista e grande conoscitore di greco Guarino Veronese (1). La sua influenza presso la corte estense contribuì all’umanesimo dei principi ferraresi, oltre ad aprire l’arte estense verso il gusto orientale, le forme bizantine, lontane dalla centralità e dalla monumentalità latineggianti: il risultato fu una commistione di astronomia di origine araba, mitologia latina e greca, alchimia, astrologia (2). Vi era infatti stata una ripresa, a partire dal tardo Medioevo e durante tutto il Rinascimento, dell’interesse per la cultura e la letteratura antica. Verso la fine del Trecento, tutta la sapienza classica fu riscoperta, rivalutata e importata grazie ai viaggi e agli interessi di nuovi intellettuali: il fiorentino Coluccio Salutati, che invitò in Italia il dotto ateniese Emanuele Crisolora; Guarino Veronese, che di Crisolora diventò amico personale; il filosofo neoplatonico Giorgio Gemisto Pletone, che fu in Italia intorno al 1438 e influì notevolmente nella diffusione del neoplatonismo.

Con Leonello d'Este (al potere 1441-1450), gli orizzonti culturali della corte si ampliarono ulteriormente. Educato da Guarino Veronese, fu in contatto con le principali personalità artistiche del tempo, tra cui Pisanello, Leon Battista Alberti, Jacopo Bellini, Piero della Francesca (dal 1448 circa) e Andrea Mantegna (in città nel 1449 e nel 1450-1451). Inoltre avviò una raccolta antiquaria e una manifattura di arazzi, creando rapporti stretti e continui con le Fiandre: a Ferrara soggiornarono alcuni grandi maestri transalpini, come Rogier van der Weyden (verso il 1450) e Jean Fouquet (verso il 1447). Lionello diede anche impulso all’Università (fondata nel 1391 dal marchese Alberto V d'Este, su concessione di papa Bonifacio IX). I primi corsi inaugurati furono Arti, Teologia e Giurisprudenza, in cui insegnarono sin dall'inizio docenti di chiara fama, come Bartolomeo Saliceto, principe dei giuristi, Guarino Veronese, che ebbe tra i propri allievi anche il futuro papa Pio II, Enea Silvio Piccolomini.

Fu durante l'epoca di Borso d'Este (al potere 1450-1471), che i molteplici fermenti artistici della corte si trasformarono in uno stile peculiare, soprattutto in pittura. Gli stimoli di base furono la cultura cortese, la razionalità prospettica e la luce limpida di Piero della Francesca, la minuziosità fiamminga. Questi elementi formarono un vero e proprio linguaggio artistico ferrarese, composto da una linea vibrante e un esasperato espressionismo. Il caposcuola del gruppo di artisti-artigiani che formavano l’Officina ferrarese era Cosmè Tura, al quale si affiancarono poi Francesco del Cossa ed Ercole de' Roberti. Pur nelle differenze individuali, le loro opere sono accomunate dalla preferenza per le immagini preziose e raffinate, caratterizzate da grande naturalismo e un dinamismo sfrenato, con profili aguzzi e un chiaroscuro incisivo che rende ogni materiale come metallo sbalzato o pietra dura. L’interesse della corte per l’astrologia e l’alchimia influenzò anche le arti, il cui linguaggio si arricchì di enigmatici intrecci simbolici.

In questo ambiente ferrarese, come in quello di Milano, era in uso la produzione dei Tarocchi. A differenti interessi culturali corrisposero differenti creazioni: orientate a un gusto classico e raffinato, e permeate di allegorie cristiane, le carte milanesi; di matrice greca, ricchi di simbolismi astrologici e alchemici, quelle ferraresi. E con differenze anche nella realizzazione: i mazzi milanesi hanno tutti più o meno la stessa misura e per la loro creazione vennero utilizzati, in alcuni casi, gli stessi cartoni: vi erano botteghe di artisti, gli Zavattari, che si dedicavano alla creazione di più mazzi per la corte sforzesca, ripresi dai tarocchi Visconti Sforza. Altri artisti attivi in tal senso furono Michelino da Besozzo e Bonifacio Bembo. Venivano realizzati con l’utilizzo di fondi dorati o argentati punzonati, dove l’immagine era disegnata, non incisa, e dipinta a tempera in punta di pennello. I loro personaggi riflettono gli abiti e le mode dell'alta società tardogotica milanese.

A Ferrara, i pittori di tarocchi furono Jacomo Guerzo, Iacopo di Bartolomeo Sagramoro, Gherardo da Vicenza, oltre a nomi più importanti quali Cosmè Tura o il Mantegna, che realizzavano le carte più importanti. Contrariamente a quelli milanesi, i mazzi ferraresi conosciuti sono estremamente diversi per ideazione, contenuto e realizzazione: diversi gli artisti, diverso il formato.

TAROCCHI VISCONTI DI MODRONE (Yale, University Library). Probabilmente uno dei primi mazzi realizzati nel XV secolo per la corte viscontea. Le carte sono ricche di storia familiare che si intreccia a quella di Milano, essendo state commissionate da Filippo Maria Visconti per il matrimonio tra la figlia Bianca Maria e Francesco Sforza avvenuto nel 1441, così come emerge dai tarocchi di Amore e Carro, nei quali viene rappresentata l’unione tra i due. Inoltre, gli emblemi araldici di entrambe le famiglie sono divisi tra i semi degli Arcani Minori. Un mazzo pensato per un uso femminile, con due figure in più per ogni seme, ovvero la cavallerizza e la fantesca; a cui vanno aggiunte le tre virtù teologali di Fede, Speranza e Carità, che potrebbero costituire un ponte tra gli Arcani Maggiori e quelli Minori, discostandosi sia dagli uni che dagli altri. Le tre carte sono accomunate iconograficamente dalla presenza, nella parte bassa, di un elemento negativo, ovvero l’eresia.

L’opera ci è giunta orfana di alcune carte, infatti ne sono presenti solo 67: probabilmente non era un classico mazzo di 78 ma forse di 89 carte, benché tante siano le tesi a proposito.

Il mazzo è caratterizzato dagli sfondi dorati, finemente lavorati a bulino per le carte figurate e d’argento per quelle numerali. Le carte, tutte dipinte a mano, misurano 189 x 90 mm.

È possibile che il mazzo sia stato realizzato da Michelino da Besozzo, artista che svolse una lunga e copiosa attività a Milano presso i Visconti e i Borromeo. Del suo influsso risentirono tutti gli artisti lombardi, sia contemporanei, come gli Zavattari, sia della generazione successiva. Le sue caratteristiche pittoriche sono il colore grasso e pastoso delle vesti, limpido nelle carni, il tratto elegante con attenzione ai particolari, il cromatismo vivace e leggero.

TAROCCHI VISCONTI BRAMBILLA (Milano, Pinacoteca di Brera). Secondo dei tre mazzi viscontei, realizzato per il duca Filippo Maria Visconti tra il 1442 e il 1447, come testimonia il fiorino d’oro coniato dal duca, presente nel seme di Denari. Sia per la realizzazione, fogli sovrapposti di cartoncino punzonati d’oro nelle carte figurate e d’argento nelle carte numerali, sia per la presenza di motti, imprese araldiche, emblemi e per l’analoga raffigurazione dei Bastoni, visti come frecce e non come clave, sia per la misura (178 x 89 mm), il mazzo Brambilla è simile al Visconti di Modrone. Inoltre, entrambi hanno analogie per struttura, decorazione ed eleganza dei tratti, tale da indurre a pensare che il Visconti di Modrone possa aver funto da modello al Brambilla.

I personaggi hanno visi rotondeggianti, quasi infantili, con minuziosi lineamenti, occhi rotondi, gote rosate appena accennate. Per i visi vengono utilizzate sfumature di rosa; nei corpi, una morbidezza di modellato e una pastosità nelle vesti, con pieghe manierate e goticheggianti. Tali caratteristiche ricordano Michelino da Besozzo, ma rielaborate in maniera ancora più elegante e raffinata: è lo stile degli Zavattari, famiglia milanese di artisti attivi in Lombardia, sotto i Visconti prima e gli Sforza poi. È possibile che l’ideatore-realizzatore del mazzo sia stato uno dei fratelli, con l’aiuto della loro rinomata bottega. Nelle immagini si riscontra una vena di osservazione dal vero, come nelle note vegetali, nei gesti e nei costumi ricavati dalla vita reale: le vesti sono ricercate, con puntigliosa descrizione dei particolari. Anche il trattamento dei cavalli, sfarzosamente bardati e con sagome nettamente profilate e la vivacità di alcuni dettagli, offrono agganci con la cultura pisanelliana. Gli stessi gesti e atteggiamenti di personaggi nobili e dignitosi si ritrovano anche nella Cappella di Teodolinda nel Duomo di Monza, decorata dagli Zavattari. Certe pose si ritrovano in alcuni personaggi realizzati dagli Zavattari in opere diverse, sintomo del ripetuto riutilizzo dei cartoni. Il mazzo ci giunge nella semi integrità di 48 carte.

TAROCCHI VISCONTI SFORZA (New York, Pierpont Morgan Library e Bergamo, Accademia Carrara). Terzo e ultimo mazzo milanese, con 74 carte. Di questo originale mazzo, indichiamo sei carte: Forza, Temperanza, Stelle, Luna, Sole, Mondo eseguite come integrazione di carte perdute o danneggiate, da un artista ferrarese alla fine del 1400; non da Antonio Cicognara, come solitamente attribuisce la critica. Espliciti i caratteri della pittura della scuola ferrarese, come il plasticismo scultoreo delle figure, una rappresentazione umana attenta al dato naturale, figure dinamiche, con contorni tesi e spigolosi. Totalmente diversa, poi, è la visione di queste sei carte rispetto all’idea originaria del mazzo, tanto che in esse ritroviamo quell’attenzione alla Grecia antica, con la mitologia e l’astronomia, tipiche della corte ferrarese.

Negli originari arcani maggiori invece, ritroviamo antiche fonti, quali Aristofane o Eraclito, e le allegorie dei Vizi e delle Virtù, categorie fondamentali nell’arte cristiana medievale in prospettiva escatologica: attraverso il trionfo delle une sugli altri, oppure il semplice accostamento antitetico, l’artista intende indurre il fedele a seguire la retta via, ora utilizzando forme vicine all’esperienza sensibile e quotidiana, ora rivestendo la scena di forzature espressioniste.

Le carte misurano 176 x 87 mm e sono composte di fogli sovrapposti di cartoncino, probabilmente pressati a stampo. Quelle senza figure hanno fondo bianco, ornato con motivi floreali in verde, azzurro e oro, contornato da un sottile bordo rosso e oro. Le figure e i trionfi hanno fondo dorato, eccetto nella parte inferiore, dipinta a terreno con erba e fiori, decorato; più su, il fondo è punzonato con motivi a losanga, aventi nel centro il sole raggiante e racchiusi entro una cornice ornata da una fila di rosette, anch’esse realizzate a punzone. La decorazione del fondo, nelle carte con figure e nei trionfi è dunque del tutto simile a quella del mazzo Brambilla, a eccezione del motivo, là a piccoli rombi e qui a rosette, all’interno della cornice. Analogamente, ritroviamo motti ed emblemi araldici sia viscontei che, in questo caso, sforzeschi.

Lo stile del mazzo Visconti Sforza si avvicina a quello del Visconti Brambilla: soprattutto per alcuni dettagli che rimandano allo stile degli Zavattari, ma qui con minor eleganza, meno cura dei particolari, con personaggi statici e privi di leggerezza. È molto probabile che il mazzo Brambilla sia stato realizzato in prima persona da uno dei fratelli Zavattari, mentre lo Sforza può essere stato un lavoro di bottega, nella quale quindi ritorna l’utilizzo di certi modelli tipici. Sintomatico del lavoro di bottega è proprio il riutilizzo dello stesso schema all’interno del mazzo di carte. È probabile che questo fosse stato realizzato per celebrare l’ascesa di Francesco Sforza, il 26 marzo 1450, alla guida del ducato di Milano, dopo la capitolazione della Repubblica Ambrosiana, proclamata alla morte di Filippo Maria Visconti.

Un altro importante indizio per la datazione è dato dal Re di Spade, che con la mano sinistra regge uno scudo sul quale s'intravede un leone veneziano rampante, aureolato e con le zampe anteriori poste sopra un libro chiuso. Ciò significava che la città di Venezia era in guerra, mentre in tempo di pace il libro era aperto alla scritta Pax tibi Marce evangelista meus. Poiché la guerra tra Venezia e Milano durò dal 1430 al 1454 e finì con la Pace di Lodi il 9 aprile 1454, è possibile ipotizzare che questo simbolo intenda riferirsi proprio a tale guerra e offre quindi un terminus post quem ben identificabile. Infine notiamo come, se nel mazzo Modrone i semi erano suddivisi tra le due famiglie, qui manchino buona parte degli emblemi prettamente sforzeschi. Le imprese delle due famiglie simboleggiano, così come per i Visconti di Modrone, la continuità tra i Visconti e gli Sforza.

Come già accennato, la bottega degli Zavattari utilizzava gli stessi cartoni per i mazzi di tarocchi, come anche per affreschi o tempere su tavola.

I cartoni del mazzo Visconti Sforza vennero riutilizzati per la produzione di altri mazzi a fruizione della stessa famiglia, come suggeriscono i loro emblemi araldici, e probabilmente destinati ad altre corti sforzesche presenti nel territorio.

Le carte in collezione privata misurano 17,5 x 8,8 cm. I bordi hanno lo stesso colore di quelli delle carte Visconti Sforza: nelle carte figurate un bordo blu, mentre in quelle numerali un bordo rosso con all'interno un sottile bordo verde. Anche lo sfondo è simile: una punzonatura identica con roselline verso il bordo esterno e internamente suddiviso in rombi entro i quali è presente anziché il sole raggiante, un fiorellino a quattro petali. La suddivisione tra fondo punzonato e dato erbaceo del Visconti Sforza è addirittura sovrapponibile alle nostre carte.

In particolare nel Cavaliere di Coppe, sulla decorazione azzurra della calza, peraltro identica nello Sforza, ci sembra di scorgere la lettera A, mentre nella calza del Cavaliere di Coppe Sforza è presente anche la lettera I, prima della A: I A. Le due lettere potrebbero alludere al nome dell’artefice o artefici: partendo sempre dal presupposto che la realizzazione sia avvenuta nella bottega degli Zavattari, le due lettere nel mazzo Visconti Sforza potrebbero alludere ai nomi di Giovanni (Iohannes) e Ambrogio (Ambrogio). Mentre nella nostra carta potrebbe alludere al solo nome di A - Ambrogio.

TAROCCHI DEL MANTEGNA (Parigi, Bibliothèque nationale de France). Mazzo realizzato a Ferrara nel 1450 per il Duca Borso d’Este, con chiaro intento celebrativo del territorio ferrarese, come dimostra la presenza dei paesaggi lacustri tipici della Ferrara di quel tempo, fatta di un fitto reticolo di corsi d’acqua. Palesi appaiono i rimandi al Mantegna, come la resa fisionomica dei personaggi, l’utilizzo dell’incisione, l’attenzione all’antico e alla mitologia greca e romana. Importanti anche le fonti per quest'opera che in sé raccoglie arte, cultura e sapienza.